William Parker Skelland, 81, will spend at least four years in prison for sexually abusing children at Burwood Boys’ Home in 1973 and 1974. Skelland was living in the United Kingdom in 2019 when he was arrested and extradited back to Australia to answer for his crimes.

Skelland and his wife were working as “cottage” carers at Burwood in the 1970s. Skelland systematically abused the children for his own “deviant, sexual gratification”.

The youngest of his victims was six and the eldest was 14-years-old.

The County Court of Victoria heard that Skelland assaulted one of the children in his own living quarters and when the boy complained to the head of the home, he was hit in the face. On other occasions, Skelland abused his victims while they were watching television, or he went into their bedrooms at night.

Judge Mark Dean said the six-year-old victim was in pain and had started to cry before Skelland stopped assaulting him.

“[The victim’s] wife attests to his isolated, reserved and weary disposition,” Judge Dean said.

“He is ashamed of what you did to him. No doubt this terror was experienced by all of your victims.”

Skelland and his wife were fired from Burwood in 1974 due to the abuse allegations. However, Victorian Police were only notified 40 years later when Skelland was identified during the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.

In Court, Judge Dean noted that Skelland had multiple health conditions as well as a paedophilic disorder, personality disorder and depression. He rejected that Skelland was remorseful for his crimes and would have to sit through a sex offender’s program to understand how he traumatised his victims.

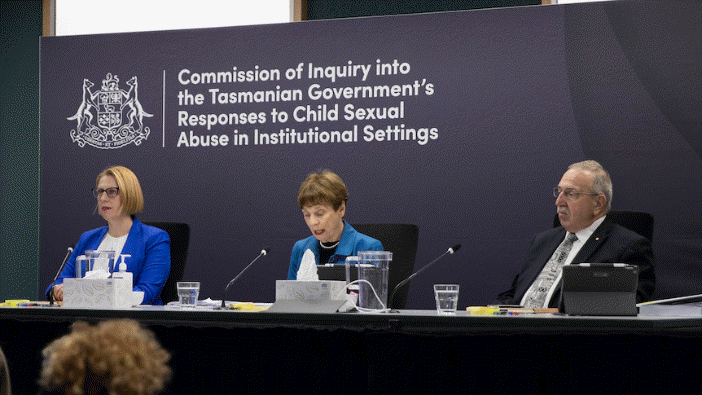

Child protection reform manager tells Tasmania’s Commission of Inquiry that the out-of-home care system is broken

Image: ABC News

Sonya Ecklemann worked as a project manager for out-of-home reform in Tasmania’s Communities Department between 2017 and 2020. In May 2022, she told Tasmania’s Commission of Inquiry that the role was “something of a reality check” and what she encountered was a system under strain.

“I was told by a senior policy person that nothing would change and that I was wasting my time. I remember looking at them and going, ‘Well if we take that approach we might as well give up now’. But they were right,” Sonya said.

“There’s a hesitancy for genuine, open consultation when I was there, there’s much more interest in trying to maintain control of the message, which I think is a sign of an organisation that’s under stress.”

“It became very apparent to me very quickly that the department had a reputation of being very closed and very defensive, its approach was often considered to be crisis-driven and reactive.”

Sonya told Commissioners that caseworkers had “ridiculous” workloads which meant they could not support children and carers adequately. She also said there was a high turnover of caseworkers — not because the nature of their work was difficult but because the organisation itself was frustrating and they were not seeing change where it mattered.

The lack of support for carers and children can cause problems for already vulnerable children.

“If it is the case that we’re not supporting our carers effectively, and the child ends up having a breakdown in the home, or multiple breakdowns in the home, then we are, as a system, magnifying those vulnerabilities to child sexual abuse, to grooming behaviours,” Sonya said.

“Because there are perpetrators out there that can pick a person a mile away who is going to be more amenable to grooming, who has unmet needs, who is isolated, who doesn’t have a sense of being loved, who doesn’t have a sense of self-worth.”

“That’s the worry that I have, that we don’t meet children’s needs early enough and, when we don’t do it well, we can actually magnify those unmet needs and those vulnerabilities in the future.”

Commission of Inquiry hears multiple cases of children being abused in Tasmanian schools

Image: ABC News

Throughout May, Tasmania’s Commission of Inquiry heard from multiple victims of school abuse. The woman shared their struggle to achieve justice and stop paedophile teachers from reoffending.

Kerri’s story

Kerri was just 7-years-old when she was abused by a teacher (known only as John) at her primary school in the 1980s. When a new counsellor came to the school, Kerri and three other girls who had been abused told the counsellor what had happened.

The counsellor believed the girls and took detailed notes. Kerri was also believed and supported by her family. However, the school principal and other teachers made it clear they did not believe her story.

“It was difficult because all of a sudden you were seen as different… or a liar, is how I felt,” Kerri said.

Kerri made a complaint to the police but she was never told what happened afterwards. In the early 2000s, Kerri was studying psychology and social work at university when she realised John was still teaching children.

“I became quite depressed and I was suicidal at the time and I moved back home to my parents for 18 months,” she said.

Kerri and three other women submitted statements to the police and John was finally charged. Just before the trial, Kerri received a phone call from prosecution services saying the trial would not be going ahead and was not given a reason why. After making several more complaints, Kerri gave up and said she had “nothing left to give”.

In 2018, Kerri was contacted by a police officer who wanted to talk to her about John.

“I nearly fell off my chair because it had been so long… someone else from the federal Royal Commission had made a disclosure and they’d reopened the case,” she said.

The case, again, went nowhere but Kerri heard John was on suspension.

Katrina’s story

Katrina was sexually abused by one of her teachers (known only as Peter) in the 1990s when she was in years 9 and 10. She told the Commission Peter was incredibly friendly with students on a camp she went on but his behaviour towards her became sexualised.

Katrina told the Commission Peter abused her at school and out of school including at his home. He also wanted Katrina to call him regularly. She was a good student and conformed to whatever her teachers said.

“They were there to teach me and to help me and at the time I didn’t really think about the whole keeping me safe thing,” she said.

“These people that for so many years have been so trustworthy, and have looked after me so well, all of a sudden I’m met with the total opposite. Even though he crossed a line, what power did I have to do anything about it?”

During class one day in year 10, another teacher took her aside and told her it was not normal for her to spend so much time with Peter. She said the conversation made her feel blamed.

“I was mortified. I was so scared because my world was about to end. Essentially, my goals, my perception of what life was going to be had just been shattered because someone knew and I feared so much what was going to happen to me.”

“They hadn’t acknowledged what they thought was going on, they did not make it stop. The abuse continued. He did not desist. I was the one that was expected to make it stop, I was the one that made it stop.”

Katrina later learned that Peter had also been spoken to but the conversation went differently. Instead of receiving blame, Peter was simply told to “watch himself”. To Katrina, this meant “keep doing it, just keep doing it better so no one notices”.

She was able to make the abuse stop by avoiding places where Peter might be and making excuses to avoid him. He would write letters to her and leave them in her locker, and he called her names in the hall if no one was in earshot.

Katrina was later placed in his classes again, which she described as “agonising”.

No one from the Education Department reached out to Katrina despite her initial disclosure in 2000, her full disclosure in 2018, court proceedings and her comments in the media. She also wrote to then education minister — now Premier — Jeremy Rockliff 16 times over 16 weeks, asking him to meet with her.

He denied meeting with her every time.

Rachel’s story

Rachel* was groomed and sexually abused by a high school teacher until her mother noticed the teacher’s inappropriate behaviour on a sporting tip in the mid-2000s. Her mother made a complaint, triggering a two-year investigation that revealed more than Rachel’s mother had initially realised.

Rachel said she was confused by her teacher’s behaviour (known only as Wayne). He made her feel responsible for him keeping his job, so she felt she had to protect him and did not disclose the full extent of the abuse for two years.

“I would cry in my bed every night going ‘why me, why me, why can’t I just tell them the truth?’” she told the Commissioners.

She was later informed at a meeting that Wayne had not breached the state service code of conduct, which is when Rachel finally had a breakdown and told them what had actually happened.

“I had my mother there, I was sitting on my hands, I was shaking, my heart was just beating so fast it was in my throat… my mum was just bawling her eyes out because it was the first time that she had heard what had actually happened to me.”

Rachel told the investigators about all the times Wayne had kissed her and how she felt pressured to kiss him, and about the times he touched her inappropriately when they were alone in his car.

The investigators asked her to demonstrate and asked her to make a statement in writing. She told the Commission she did not feel the investigators were listening to her.

Wayne could not be charged with assault with indecent intent because the complaint must be made within 12 months of the incident. Rachel later saw in the newspaper that Wayne had not breached the state code of conduct and had taken up another teaching position.

“I was gutted, I felt betrayed, I felt neglected… I didn’t understand; I had just told [the investigators] what he had done to me and he is still allowed to teach?”

Get the justice you deserve with Kelso Lawyers. We want to hear your story. Call (02) 4907 4200 or complete the online form before you accept payment from the National Redress Scheme.

Feature Image: The Guardian