The orphanage was established in 1885 to accommodate children transferred from St Joseph’s Orphanage in Bucasia, Queensland.

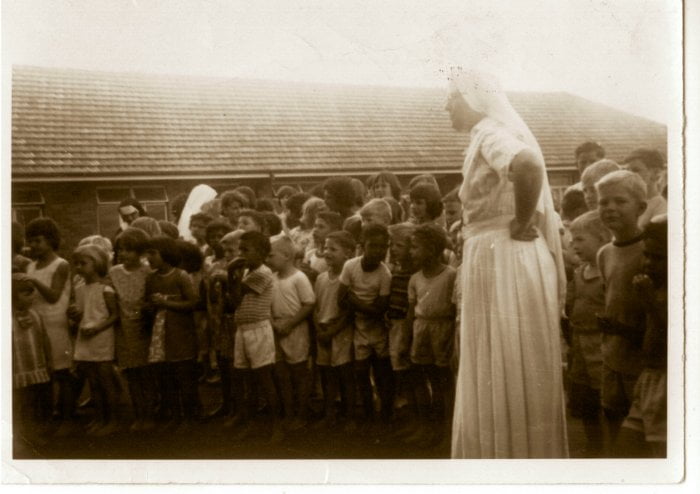

Managed by the Sisters of Mercy, with priests provided by the Catholic Diocese of Rockhampton, 4,000 boys and girls lived at the Neerkol location over their century of operation, including hundreds of migrants from Britain.

In 1998, Former Queensland Governor Leneen Forde launched an inquiry into instances of abuse at Neerkol. The inquiry revealed the nightmarish living conditions at Neerkol and the harsh punishments handed down by the nuns over the years.

64 former residents and staff members gave evidence at the Forde Inquiry.

In 2015, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse delved deeper into the abuse at Neerkol.

13 former residents in their 50s, 60s, 70s and 80s gave evidence against the Sisters of Mercy.

Not a single survivor was able to contain their tears as they recounted horrendous instances of abuse, including but not limited to:

- Public floggings

- Starvation and withholding food/water

- Raping & sodomising the children

- Walking on children in high heels

- Beating a boy’s genitals with a ruler while telling him his penis was “the devil”

- Forcing bed-wetters to stand in the dining room with their urine-soaked sheets draped over their heads while the other children ate breakfast

- Forcing boxing matches between girls and boys for the nuns’ entertainment

- Using a cat o’ nine tails to horse-whip runaway boys

- Forcing children to drink their own urine for hydration

The nuns started breaking the children’s spirits upon arrival

Siblings were separated, and their possessions and comforts were removed.

The children were known as numbers or exclusively by their surname.

Birthdays weren’t recognised, except for children who were favoured by the paedophile priests who served at the orphanage.

David Owen arrived at Neerkol in 1939 at the age of five months old.

Throughout his childhood, David – known to the nuns and priests as “number 34” – was repeatedly and viciously raped by Father John Anderson. The sisters would escort David to Anderson, knowing David would be sexually, physically and emotionally abused.

Anderson told David he needed to improve his Latin. He would be escorted to the presbytery for private lessons, but instead, he would be sodomised by Anderson.

If David refused to see Father Anderson or reported the abuse, he would be savagely beaten by the nuns, who accused him of lying: “you filthy animal, how dare you speak about a priest like that!”

David was also an altar boy and was required to assist Father Anderson when he performed mass in outlying parishes once a month. On these trips, Father Anderson would abuse David.

When David was 15 years old, he started working for Mr Hanrahan, a local farmer. However, David was still being abused by Father Anderson, and on one occasion, he began bleeding from the backside.

Mr Hanrahan asked what had happened, and David told him about Father Anderson.

Mr Hanrahan took David to the Child Welfare Department and met with Mr Paterson, the local welfare officer who David knew from Neerkol. Mr Hanrahan told Mr Paterson he didn’t want David working at his farm because he had an 8-year-old son.

David told Mr Paterson about the abuse, and he became furious. He drove David back to Neerkol – Mr Paterson had spoken to David about the bleeding in the past and told David not to tell anyone about the abuse.

“He told me I was a good worker but I couldn’t go out to service until I stopped bleeding from the backside,” David said.

Mr Paterson had also told David he needed to wait until he had stopped bleeding before he could go out to service from Neerkol.

Mr Paterson was a friend of Father Anderson, and David recalls two men dining together in the presbytery when Mr Paterson came to complete is required visits.

In the 1990s, David reported the abuse to the police. Around this time, David received anonymous, threatening phone calls. He also received a bullet in his mailbox.

By the time the Forde Inquiry & Royal Commission came around, very few of the nuns, priests and staff members were alive to face their punishment

Father Reg Durham was imprisoned for a few months in the 1990s before he died. Groundskeeper Kevin Baker was charged with dozens of child abuse offences.

The Diocese and the Sisters of Mercy settled a compensation claim made by 72 former residents with a $790,910 payout – but many survivors say it’s not enough.

The survivors of Neerkol have suffered life-long conditions and mental health problems, including but not limited to illiteracy, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, rotted teeth, deafness from being hit over the ears, and the inability to form intimate relationships.

“No amount of money can ever give my back my childhood, my loss of confidence, my lack of formal education, dignity, self-esteem or self-worth,” one of the survivors said.

At least one former resident, 62-year-old Diane Carpenter, has found some solace from the investigation into Neerkol.

“I feel as though through the royal commission that I am finally being heard after this process has taken over 20 years,” Diane said.

“I realise I can’t change history but want to prevent similar things happening in the future. Children desperately need to be protected.”

St Joseph’s Home in Neerkol was allowed to operate for 93 years. Thousands of children passed through the orphanage. Many never learned to read or write; many were starved and tortured. Most survivors have had to live with irreparable emotional and physical damage.

Neerkol was a dark, disturbing chapter in Australia’s history, and the remaining survivors should be compensated for the nightmarish treatment they were forced to live through.

Image: Lewis Blayse