The 7 worst children’s institutions in Australia. Neerkol Orphanage, Riverview, Westbrook, Boystown Beaudesert, Wilson Youth Hospital, Alkira and Enoggera.

Image source: Daily Telegraph

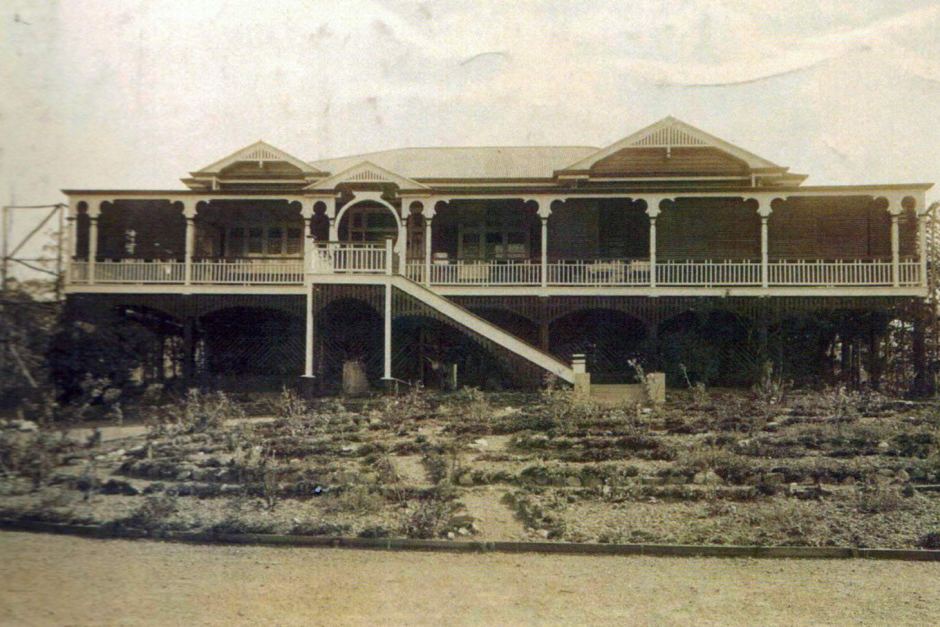

St Joseph’s, Neerkol was an orphanage for boys and girls near Rockhampton. Everyone just called it ‘Neerkol’ after the name of the nearby township.

It was run day to day by the Catholic Sisters of Mercy. The orphanage and the Sisters were subject to great scrutiny by the Royal Commission. The Catholic Diocese of Rockhampton was also involved with the orphanage. Priests from the Diocese frequented the orphanage to say mass for the nuns and the children. The children were a mixture of government-appointed State wards and those voluntarily handed over to the nuns by parents who were not coping.

The abuse of children at Neerkol went on for decades. Priests raped the boys and girls on a regular basis while nuns often dispensed brutal punishments. There was no compassion. They were not laughing nuns. It was far from a loving and safe place. It was a dark and disgraceful place way out in the country.

There were so many complaints that the Royal Commission travelled to Rockhampton for a case study hearing. Throughout hearings into the orphanage, the Royal Commission heard how children were repeatedly raped, sodomised and physically abused in their time at the institution.

One victim was raped over 100 times, starting when she was just 11 years old.

The Sisters of Mercy, the Catholic Diocese of Rockhampton and the Queensland Government have all faced strong criticism for their poor responses to complaints of abuse. Neither the local bishops, the nuns or the government showed any interest in taking the complaints seriously. One former resident wrote a book in the 1990’s about abuse at the orphanage. But the bishop at the time told the Royal Commission he didn’t bother to read it.

If the children weren’t being sexually abused by the priests, they were being physically and psychologically abused by the nuns, If the children dared to speak out against the priests’ abuse against themselves, or other children, they were punished – some sexually assaulted by the very people they saw abusing others.

Image source: The Queensland Times

Riverview was run as a training farm where boys learned skills which might prepare them for employment when they left. The Salvos were paid by the government to look after the boys. They were paid a fee for each boy. The more boys they took on the more money they got.

Five notorious predators including Victor Bennett, Lawrence Wilson, Donald Schultz and John McIver were allowed to move around Salvation Army Homes, including Riverview and Alkira, despite repeated complaints of abuse.

These men were allowed to roam between the Homes, picking out boys to abuse or send elsewhere to suffer abuse.

One particular victim had been placed in an orphanage in NSW when he was four. At age 11 he was moved to St Vincent’s Boys Home at Westmead, Sydney where he was sexually abused by a Marist Brother. He ended up at Riverview in Queensland where: “I felt Captain Bennett hated me from the start.”

There was evidence that the Government was aware of the appalling conditions at Riverview at least as early as 1970, but failed to act to protect the children. Reports from the 1970s show that the Government was even aware of multiple incidents of rape in the home, but declined to cancel the Riverview’s licence because the Government was in ‘urgent need of accommodation’ for unwanted children.

Image source: The Chronicle

Westbrook Farm was a notorious Queensland institution for boys with a dark history of beatings, neglect and rape. It was known as “the most feared “reformatory” in the country.” The isolated Farm was the subject of a Foxtel documentary with an introduction by former Premier Anna Bligh.

Run by the Queensland State Government from 1900 until its closure in 2012, Westbrook was a place of hell for young boys, where whippings, starvation and deprivation of medical care were commonplace. There was a long history of sexual abuse, with ex-residents stating abuse in the showers was ‘commonplace’.

Some boys were beaten till they bled.

Others had their hands broken so they couldn’t write.

One survivor of the institution has gone on to write a book on the abuse that occurred in the reformatory, letters from parents that were never given to him, visits that were turned down – all done to break the boy’s spirit.

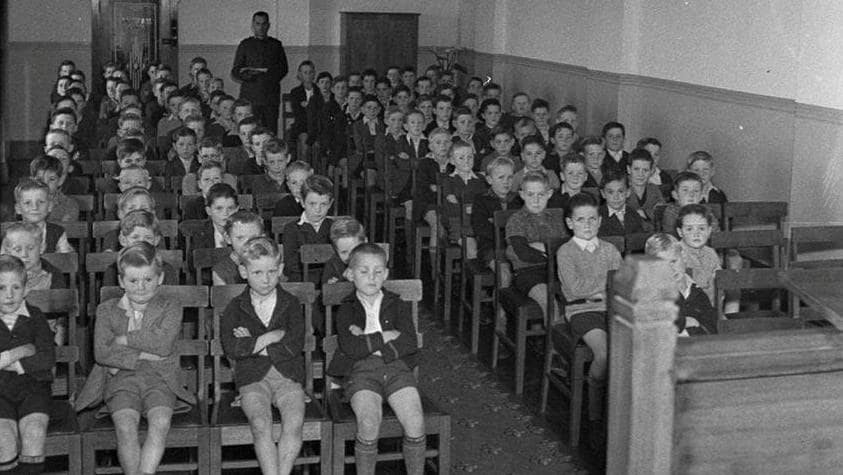

Boys Town was run by the De La Salle Brothers at Beaudesert from 1961 to 2001. BoysTown Beaudesert housed disadvantaged boys in their early teens and was established by Monsignor Owen Steele, who was the priest in charge of St Mary’s Catholic parish at Beaudesert at the time.

It was staffed by the Brothers, assisted by some lay employees and received state government funding. The Brothers received a payment for every boy they housed at Boys Town. The residential accommodation closed in 2001.

More than 1600 boys passed through it during those 40 years.

Boys Town had the highest number of sexual abuse claims against it than any other single Catholic institution in Australia. It featured in the Child Abuse Royal Commission but was not the subject of a particular Case Study hearing like Neerkol, Riverview and Alkira.

In 2012 the Nine Network’s 60 Minutes ran a story on Boys Town which included interviews with former residents. The next year, Queensland Police set up a special operation named Operation Kilo Lariat to investigate the allegations. Since then, three former De La Salle brothers have been charged with child sex offences. Research shows there have been a massive 219 plausible claims made against the Catholic Brothers and staff who worked at Boys Town.

Wilson was a State-run institution for the detention of children usually via the Children’s Court. The Forde Inquiry found that children’s needs and educational entitlements at Wilson were neglected, that they were stigmatised as criminal and psychiatric cases, and they were exposed to the significant risk of physical and sexual abuse.

In 2017 a former officer at Wilson was charged in relation to 41 offences between 1981 and 1995. The charges included indecent treatment of boys, carnal knowledge and deprivation of liberty.

On my first visits to Wilson, I could not believe what I saw taking place. Most, but not all, of the young inmates found their way into Wilson through the Children’s Courts. Many young people – in fact, most of the girls on their first admission – were placed in Wilson for non-criminal offences…

Wilson was a place of institutionalised violence. Most children had not committed serious crimes, contrary to what the Minister for Children’s Services, Mr John Herbert, often used to say: “Wilson is full of murderers, rapists and arsonists”…

All young people who had the misfortune of entering Wilson were treated psychiatrically which often meant in practice that they were treated with drugs. The result of this in many cases was that these young people were released from Wilson with a drug habit…

When a young person’s dignity had been attacked and destroyed, it is very difficult and in many instances impossible for them to recover their dignity and live a ‘normal’ life.”…

Staff were also using drugs to control the young people. Young people were often injected with sedatives. If some staff wanted to have a quiet shift, they were not above giving sedatives to their young charges. Some young people who did not have a drug problem when they entered Wilson certainly had a raging habit by the time they were discharged.

Image source: ABC

The Royal Commission also received evidence confirming that the Queensland Government was aware of serious concerns about the home, but turned a blind eye. It is also alleged that the Alkira home was part of a paedophile ring. Boys were allegedly picked up from the home where they were then abused in Brisbane, before being transported to Sydney to be abused by wealthy men.

Boys were then responsible for making their own way home.

Salvation Army whistleblower, Major Clifford Randall, spoke to the Royal Commission about the abuse senior Salvation Army personnel dealt out to the boys at the Indooroopilly home.

”McIver just went crazy … he slammed the boy into the wall, hitting his face and dislocating his shoulder.

”I threw him into his chair and said ‘If you want to hit somebody, hit somebody your own size’.”

Enoggera Boys’ School (sometimes called the ‘Church of England Boys’ Home’) was opened in 1906 and managed through the Anglican Archdiocese of Brisbane.

In 1940, Enoggera was licensed under the State Children Act 1911 – meaning the Church would be paid by the government to look after the children.

While Enoggera should have been a safe space for boys in need, it quickly became a black spot on the map of Queensland.

Throughout the 1960s, Enoggera was also home to a trainee policeman who volunteered to help care for the children. His name was Graham Noyes. He sexually abused the boys on a regular basis.

The Royal Commission heard from former state ward, Dennis Dodt, who reported Noyes once pinned him to a bed and forced his penis into Dennis’ mouth until he blacked out. Dennis was seven-years-old at the time.

After finishing school, Dennis reported the abuse to a police officer in 1993. Several years later, Dennis was contacted and told the authorities were investigating Noyes for child sexual abuse charges.

In 1999, Noyes was indicted on 53 child sex abuse offences involving ten victims. He was acquitted three times but was found guilty in the fourth trial. Strangely, Noyes was ultimately convicted of offences unrelated to any of the crimes he committed at Enoggera.

These stories of abuse are horrific. It’s horrific to think young boys were so regularly abused without anyone to save them.