For years, the Anglican Diocese of Newcastle allowed child sexual abuse to go unchecked. The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse exposed a devastating pattern of abuse, cover-ups and institutional failure. What was uncovered in Case Study 42 wasn’t just the story of a “few bad apples”—it was a complete failure of leadership and accountability across generations of Church officials.

Children were harmed. Survivors were ignored. And Church leaders chose to protect the reputation of their institution instead of the safety of those in their care.

A toxic culture of power, secrecy, and fear

The Newcastle Diocese followed a traditional Anglo-Catholic structure where bishops and priests were treated with absolute authority. This made it almost impossible for children to question, challenge or report abuse.

Many victims were groomed into silence, and even when reports were made, they were often dismissed or ignored.

The Royal Commission found that several of the most dangerous offenders, including ordained men like Peter Rushton, George Parker, and Allan Kitchingman, had trained together at St John’s Theological College in Morpeth. The College was the Diocese’s own seminary. It has been described as having a “closed” and “controlling” culture, which may have helped enable the network of abuse that followed.

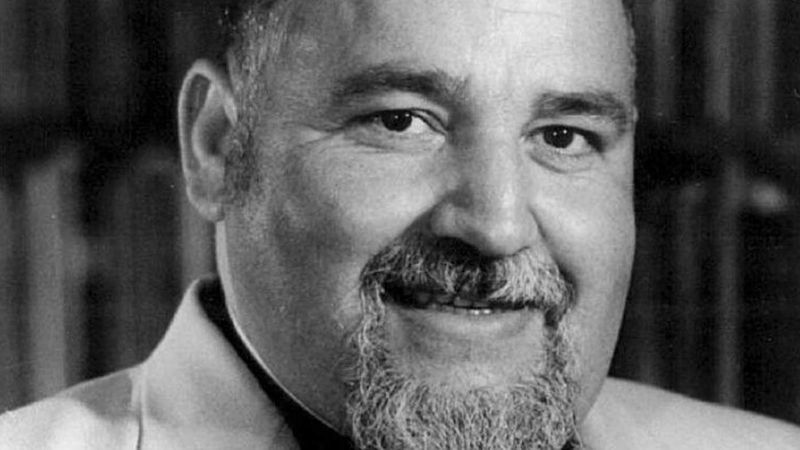

Investigated Offender: Father Peter Rushton

Father Peter Rushton was one of the most senior figures in the Diocese. He was never convicted, but the Church now accepts he was a serial abuser. Multiple victims told the Royal Commission that he raped them repeatedly as children.

One survivor, Paul Gray, said he was just 10 years old when Rushton began sexually abusing him. He also recalled being trafficked by Rushton to other men and raped at church-run camps and the infamous St Alban’s Home for Boys.

Despite these horrific accounts, Church leaders continued to promote Rushton. Even when child pornography was found among his possessions in the 1990s, no report was made to police. Instead, he was allowed to hand over whatever material he chose, and later burned hundreds of tapes with the help of another priest.

Investigated Offender: Jim Brown

James Michael Brown worked as a Church youth worker and lay preacher. He was closely associated with Rushton, and the two shared access to boys through church-run programs and foster care.

Brown was eventually convicted in 2011 of sexually abusing 20 boys over 30 years.

One of those victims was Phillip D’Ammond, who lived at St Alban’s as a teenager. Brown took him home on weekends and sexually abused him. D’Ammond later told the Commission that Brown became his legal guardian—a move that went unchallenged by the Church, even though concerns had already been raised.

The Church had known about Brown’s behaviour since at least the late 1970s. But instead of protecting children, Church leaders let him keep working with them.

Brown died in 2019. As recently as 2020, the Anglican Bishop of Newcastle, Peter Stuart, said that Brown’s crimes were appalling.

“He was able to move from one place to another and do great harm. The Diocese of Newcastle should have known more about James Brown offending at an earlier point and taken action clearly to prevent his further offending.”

“Every church, every organisation needs to do its best to make sure that people do not move from organisation to organisation.”

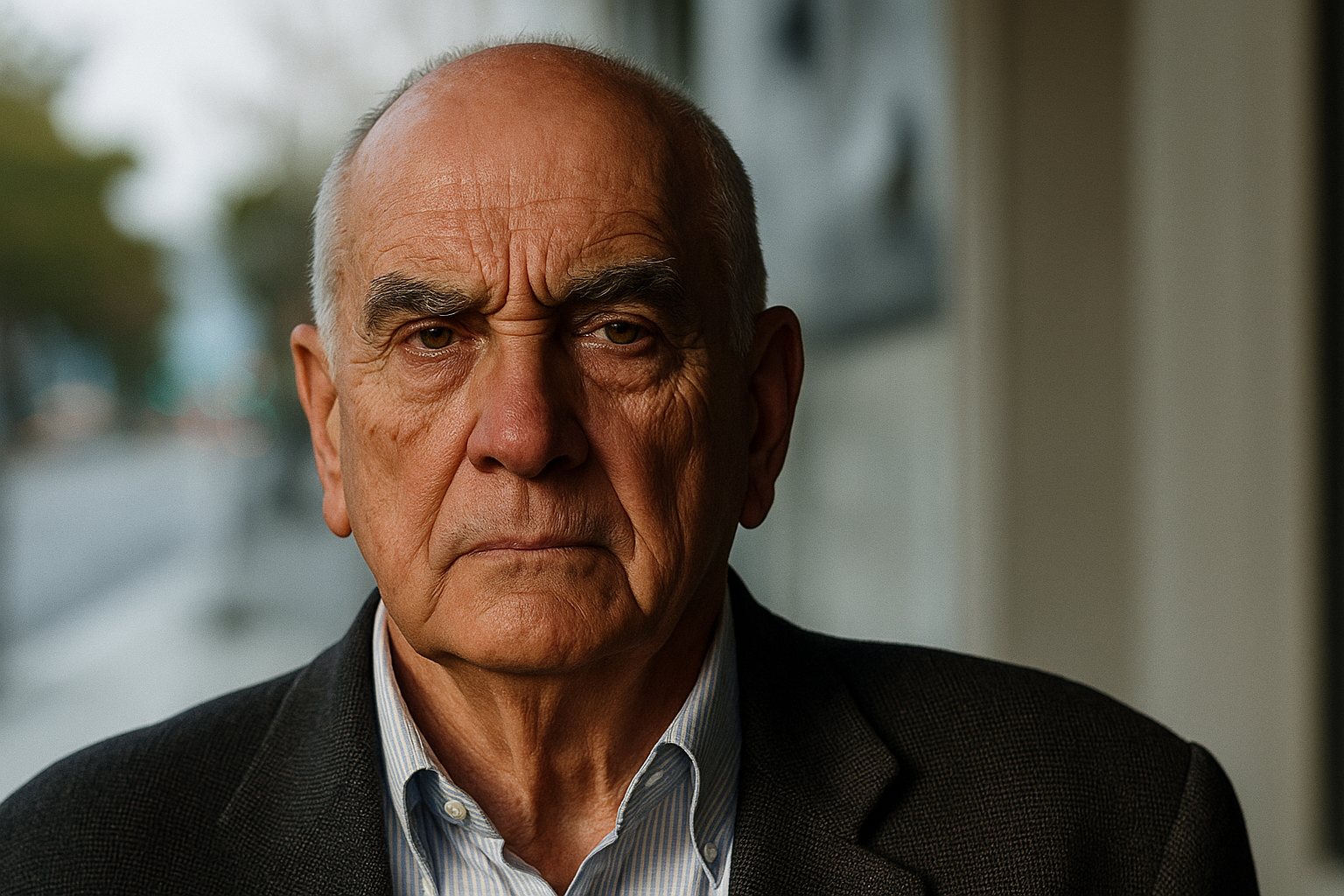

Investigated Enabler: Bishop Roger Herft

The Church’s internal handling of complaints was secretive and highly controlled.

Bishop Roger Herft led the Diocese from 1993 to 2005 and created a hidden complaint system using sealed “yellow envelopes.” These envelopes—stored in a locked cabinet—held reports of abuse and misconduct. Only a handful of people had access.

Most reports were never acted on, and few were passed to the police.

When questioned, Bishop Herft admitted he had been told of at least 24 allegations of child sexual abuse. Yet only three were formally reported. Many complaints involved serious concerns about known offenders like Rushton and Brown.

In practice, this system protected the Church, not the children. It allowed senior officials to appear to be managing complaints while doing little or nothing to stop the abuse.

Investigated Offender: Father George Parker

In the 1970s, two altar boys—brothers known as CKA and CKB—were sexually abused by Father George Parker. Their mother reported the abuse at the time, but the Church did not act.

Years later, one of the brothers contacted the Diocese again. He spoke directly with Dean Graeme Lawrence and Bishop Herft and detailed the abuse. Herft later admitted he had received enough information to go to the police but chose not to.

Even worse, when the brothers eventually went to the police and Parker was charged, two of the Church’s most senior legal advisors defended Parker in court.

These were the same men who had previously advised the Diocese on how to respond to the survivors’ original complaints.

This clear conflict of interest sent a message to the victims that the Church was more interested in protecting itself than helping them.

Investigated Offender: Dean Graeme Lawrence

Dean Graeme Lawrence was the most powerful and fearful figure in the Diocese, serving as the Dean of Christ Church Cathedral from 1984 to 2008. During that time, multiple allegations of child sexual abuse were raised against him.

The Royal Commission found that between 1995 and 1999, senior Church leaders were warned on at least three separate occasions that Lawrence had allegedly abused boys. No action was taken.

In one case, youth leaders told Bishop Roger Herft that two boys had made serious allegations. Herft admitted he didn’t report, investigate, or manage the risk. Other complaints, including one passed on from a Sydney Anglican minister, were also ignored.

Lawrence denied the allegations and stayed in his role for decades. He was a charming intellectual with enormous influence over people. Bishops and others were afraid to cross him. He seemed to be bullet proof. Survivors said this made them feel the Church had sided with the abuser.

He was finally defrocked in 2012, through the Anglican Church’s professional standards process, not by the Newcastle Diocese. By then, the damage was done. The Royal Commission found that the Diocese’s inaction had allowed Lawrence to avoid accountability for years.

Bishop and survivor forced to resign after advocating for change

In 2014, Bishop Greg Thompson took on the leadership of the Diocese. He was the first Church official in Newcastle to publicly acknowledge that he had been sexually abused by none other than Bishop Ian Shevill, a former head of the Diocese.

Thompson began to change the culture of silence. He met with survivors, called out past failures, and tried to hold abusers and Church leaders accountable—but his reforms were met with hostility. Some members of the Church accused him of fabricating his story. Others campaigned against him.

Eventually, Thompson resigned, saying the backlash had made his position impossible.

“In those intimate moments in Church—it is my cathedral—having people turn their backs on me sends a strong message that I’m not safe in that place and that there are consequences if I do not follow what they want me to do. Public harassment. Public shame.”

“When I started this journey to right the wrongs of child abuse in the Diocese, I didn’t expect to be in this position, nor did I expect to uncover systemic practices that have enabled the horrendous crimes against children.”

“The decision to resign was not an easy one; it weighed heavily on my heart. However, I must place the wellbeing of my family and my health above my job.”

His resignation marked another tragic moment in the Diocese’s long history of choosing silence over justice.

How survivors were affected by the abuse

The impact of the abuse carried out in the Anglican Diocese of Newcastle was devastating and long-lasting. Many survivors experienced deep emotional, psychological, and physical trauma—not just from the abuse itself, but from the Church’s repeated failure to believe or support them.

Some survivors reported severe mental health struggles, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress. Others turned to drugs or alcohol to cope with the pain. Relationships with family and friends often broke down, and many struggled to hold steady jobs or feel safe in their communities.

Paul Gray, who was abused by Father Peter Rushton from the age of 10, said he repressed the memories for decades. When they resurfaced in 2010, he had a severe mental breakdown.

Another survivor, known to the Commission as CKA, said the Church’s handling of his abuse was as harmful as the abuse itself. He tried to report what had happened multiple times, only to be ignored or dismissed. When his abuser was finally charged, Church lawyers stepped in to defend the priest, leaving CKA feeling betrayed all over again.

Others told the Commission they had felt shame and isolation for years, believing they were alone. In many cases, it wasn’t until the Royal Commission that they were finally heard.

The failure of the Church to act not only allowed abuse to continue, but it also compounded the suffering of survivors for decades. The harm extended far beyond childhood, shaping the course of entire lives.

Kelso Lawyers can help you seek justice

If you’ve experienced abuse—whether within the Anglican Diocese of Newcastle or another institution—you are not alone, and you are not powerless. You have the right to speak up, to be heard, and to seek justice for what was done to you.

Our team is here to listen without judgment and to guide you through every step of the process. We’ll help:

- Understand your legal options, including compensation and redress

- Assess your records and documents for eligibility

- Make a claim against the institution that failed to protect you

- Navigate the National Redress Scheme (if eligible) or consider alternative pathways offering greater recognition and compensation.

You deserve truth, acknowledgement, and real accountability from the institution that betrayed your trust. Contact us if you want to make a claim or share your experience. We can help you decide what path is best for you and ensure you don’t settle for less than you’re entitled to.