WARNING: This article includes references to suicide which some readers may find upsetting. Reader discretion is advised.

The passing of legislation in 1864 allowed Victorian children to be removed from parental care if they were thought to be “neglected” or they had been charged and/or convicted of a criminal offence (making them a “juvenile offender”). These children were labelled “wards of the department”, “wards of the state”, or “state wards”.

Before 1954, charitable and religious organisations “cared” for children who had been removed from their parents. This included organisations like the Christian Brothers and the Sisters of Mercy.

Since 1954, the Department of Health and Human Services has been responsible for all children in state care, but between 1954 and 1970, the Director of the Department was the legal guardian of all children in state care. The Director had the power to place children in state-run institutions — initially, this was just the Royal Park Receiving Depot for Girls and Boys (later renamed Turana Youth Training Centre).

The Victorian Commissioner for Children & Young People, Bernie Geary, has since described these institutions as “barns for children” and claimed, “if we had more foster carers who were better resourced, and as a consequence were more accountable, these children would be cared for not in barns with other children who are needy, but in home-based care”.

Children were treated worse than criminals in Victoria’s state-run institutions. This article exposes some of the worst offenders and explains the Royal Commission’s findings on facilities like Turana, Baltara and Winlaton.

Offending facilities

Image: Find & Connect

In the 1960s, the Victorian Government was forced to open more institutions as Turana Youth Training Centre had become overcrowded. These institutions included state-run reception centres, remand centres, youth training centres and children’s homes.

A disturbing number of these institutions have become infamous for the poor treatment of residents and inmates. Children were separated from their siblings, isolated, beaten and sexually and psychologically abused. This is a far reach from the safety and care these vulnerable children were hoping for, having come from already broken, unstable homes.

Below, we have exposed six of the worst offending facilities in Victoria.

| St Vincent de Paul’s Boys’ Home | Nazareth House Girls’ Home |

|---|---|

| Baltara Reception Centre | Turana Youth Training Centre |

| Allambie Reception Centre | Winlaton Youth Training Centre |

St Vincent de Paul’s Boys’ Home

Image: CLAN

Established in 1854, St Vincent de Paul’s Boys’ Home was Melbourne’s first Catholic orphanage and was run at different times by the St Vincent de Paul’s Society, the Sisters of Mercy and the Christian Brothers. It offered temporary accommodation for orphaned, abandoned, destitute or neglected children.

Bashings and sexual abuse were common during the 1960s. One survivor was sent to St Vincent de Paul’s after he was found living in a bus shelter with his mother and brother. He was often bashed for not eating all of his dinners or for wearing his clothes the wrong way, and by night, he was often taken from his bed to a Christian Brother’s bed.

Siblings were separated, and the children were treated as inmates. Rather than receiving an education and genuine care, they were forced into manual labour.

There have been 114 claims of child sexual abuse perpetrated by the staff.

St Vincent de Paul’s Boys’ Home closed in 1999.

Nazareth House Girls’ Home

Image: The Courier

Nazareth House Girls’ Home in Ballarat opened in 1888 to cater for older Australians and girls aged between six and 16. The Home peaked in the 1950s when it housed around 100 girls.

Many former residents described Nazareth House as a “nightmare”. One of Australia’s most notorious paedophile priests, Father Gerald Ridsdale, was a visiting chaplain at the Home in the 1960s. The girls could sense he was evil — the nuns were submissive around him, and he would take girls away whenever he pleased.

One of the girls he targeted tried to commit suicide by trying to jump out a second-storey window in the middle of the night. The other girls had to form a barrier to stop her until the nuns came in and beat her.

The nuns also doled out horrific physical and emotional abuse. Girls who wet themselves were forced to lick up their own urine, and one girl nearly drowned after a nun held her head down in a sink full of water.

Nazareth House stopped “caring” for children in 1976 as numbers were diminishing. At that time, the girls were sent to Hayeslee House in Ballarat. Nazareth House remains as an aged care facility.

Baltara Reception Centre

Image: Finding Records

Baltara Reception Centre was established by the Victorian Government in 1968. It was on the same campus as Turana Youth Training Centre but was considered a separate entity. In the 1970s, Baltara functioned as a long-term facility for boys who had experienced placement breakdowns or unsuccessful returns home. In the 1980s, Baltara was repurposed as a youth training centre before finally closing in 1992.

Baltara was described as overcrowded, and boys were often made to sleep on mattresses on the floor because no beds were available, and younger boys were placed with older children who were either known or convicted sex offenders or were known to have behavioural problems.

When the boys were not abusing each other, they were abused by the officers who worked at Baltara. The officers would also punish the boys for minor infringements and place them in solitary confinement.

Baltara closed in 1992.

Turana Youth Training Centre

Image: Find & Connect

Turana Youth Training Centre was the sole government-run reception centre for children in state care until 1961 when Allambie became Victoria’s main government reception centre.

The boys at Turana were seen as “prey” to the officers and were sexually abused near-nightly. Bullying was also a way of life, and on one occasion, a boy was subjected to electric shock treatment for reporting sexual abuse. Another inmate (who identified as female from age 14) was sexually harassed and abused by an officer after escaping a near-sexual assault by her male roommate.

In 2018, former superintendent (1968 to 1970) David Green admitted that no steps were taken to protect the inmates from sexual abuse at the hands of officers at night. He relied on trust alone that the officers would do the right thing, and he was more concerned the boys were engaging in sexual activity with each other.

“I depended upon the trust and trusted – had to trust – the integrity of the officers who were on duty at the time,” he said.

“I was focused on the child-to-child behaviour of boys or young men being locked together in different types of nightly sleeping arrangements. I tried to take some measures with respect to dealing with those situations, but some of them were impossible to deal with.”

Turana closed in 1993.

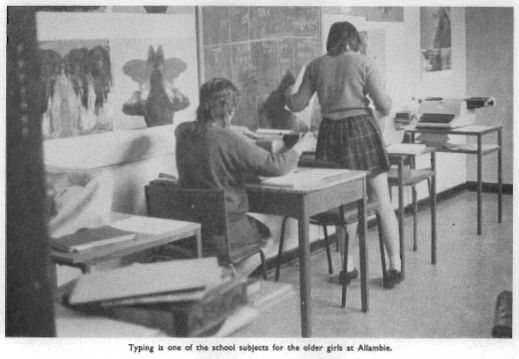

Allambie Reception Centre

Image: Find & Connect

Allambie Reception Centre opened in Burwood in 1961 and soon became the Victorian Government’s main reception, treatment and classification centre for children, babies and toddlers in state care. It was an alternative to the overcrowded Turana Reception Centre.

Children were sent to Allambie following a breakdown in-home release, foster care or a children’s home placement. Siblings were not always kept together — they were often separated into different sections of the Centre based on their age and were not allowed to see each other, or their time together was limited. Some inmates recalled sneaking out at night just to see their siblings.

During the Royal Commission, there were allegations of physical and sexual abuse at Allambie.

Allambie closed in 1990.

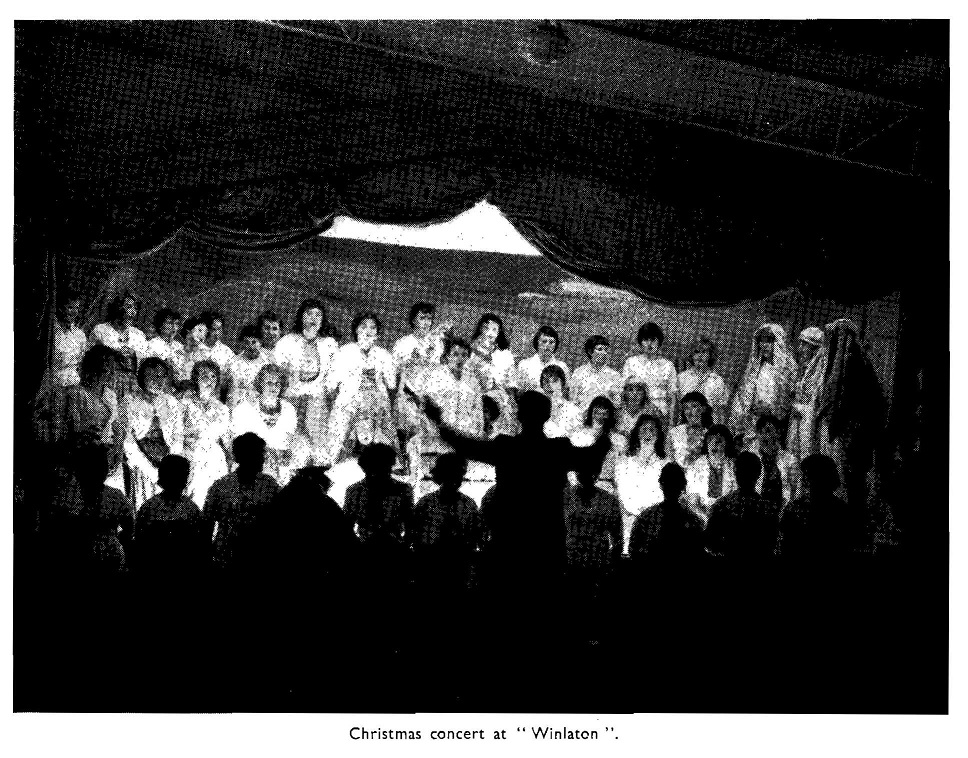

Winlaton Youth Training Centre

Image: CLAN

Winlaton Youth Training Centre was a government-run facility used to house neglected girls under the care and protect orders as well as some juvenile offenders.

Many of the officers at Winlaton were inexperienced and unqualified to work with children and often didn’t believe the inmates when they reported sexual abuse. One of the girls was being repeatedly sexually abused by her own father, but he was still allowed to visit despite her complaints. Her ward file simply stated it was not a normal father-daughter relationship.

She said she was treated like “a perpetrator, not a victim”, and no one did anything to help her. Unfortunately, this was common for the inmates at Winlaton.

Dr Eileen Slack was the superintendent of Winlaton between 1978 and 1991. It wasn’t until 2015 that she found out five girls had been sexually abused under her care. Dr Slack choked back tears and apologised to the survivors while submitting evidence to the Royal Commission.

“My ignorance is inexcusable. I want to sincerely apologise to each and every victim of this insidious and inhumane abuse,” she said.

“I feel unable to express my horror and to express my deep shame that you experienced sexual assaults with me as your superintendent… as your superintendent, each and every one of you had the right to expect my protection.”

Winlaton closed in 1991.

The Royal Commission investigated Turana, Winlaton and Baltara in 2015

Image: Royal Commission

Over two weeks in August 2015, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse inquired into the experiences of former residents at Turana, Winlaton and Baltara between the 1960s and 1990s.

The Royal Commission heard evidence from 13 former residents of these facilities. They spoke about the physical, psychological and sexual abuse they experienced at the hands of staff members, social workers and other residents and the trauma’s impact on their lives. Most survivors continue to suffer from depression, drug and alcohol abuse, and difficulties maintaining relationships with others.

The Commissioners also found:

- Residents were rarely visited by their allocated social worker or didn’t know who they were. Social workers were also not trained to prevent or facilitate the reporting of sexual abuse.

- Some residents reported sexual abuse but were not believed or called a “dobber”. Other residents were forced to remain silent or were too afraid to come forward.

- Former staff members said that the institutions had a culture of command and control rather than focusing on the welfare of the residents. This “old-school” system of brutal care often led to and allowed the abuse.

- Former staff members said they did not feel trained or equipped to work with children. Many were ex-army, ex-police officers and other imposing or authoritarian individuals. One staff member at Baltara was recruited from the United States and was later found to have been convicted of child sex offences in his home country.

- The institutions were overcrowded and understaffed, leaving many residents unsupervised. Several former residents said they were placed far from staff offices or in areas out of sight or inaccessible by staff members, leading to incidents of abuse between residents. Some bedrooms could only be observed through a small observation window in the door.

- The Department of Health and Human Services did not have policies, procedures or practices for receiving and responding to reports of child sexual abuse before the 1980s. In the 1980s and 1990s, policies were introduced but were not adequate for dealing with complaints of sexual abuse.

- The Department of Health and Human Services provided little or no oversight of the institutions. Complaints of sexual abuse towards residents were delegated to senior staff members of the institutions, who were not equipped to respond to them. It was also found that senior management failed to report complaints to Victoria Police.

During the public hearing, Dr Varughese Pradeep Philip, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services at the time, issued a formal apology to former residents of these institutions.

“I acknowledge that Turana, Winlaton and Baltara were institutions that were run and managed by the Department. The Department could and should have done more to protect children from the harm that they experienced as a result of unacceptable poor practices and failings whilst under the care of the state,” he said.

“I offer my sincere and unreserved apology to all who have been affected by these failures and unacceptable practices. I acknowledge the devastating and ongoing effects that physical and sexual abuse has on children.”

The Department failed miserably to protect residents in state-run facilities — it’s time to seek justice

By the mid-1990s, most state-run facilities like Turana, Winlaton and Baltara had closed. There are now just two youth justice centres in Victoria — Melbourne Youth Justice Centre and Malmsbury Youth Justice Centre.

Dr Philip said sexual abuse still occurs in these centres and is an area that requires ongoing vigilance. Management is overseen by the Commission for Children and Young People and the Victorian Ombudsman, with various preventative procedures enacted to better protect the inmates.

The Department of Health and Human Services has acknowledged that it failed former residents of their children’s homes and youth centres and has issued a formal public apology. However, this will never be enough for survivors who have had to live with the trauma of physical, emotional and sexual abuse at the hands of adults who were supposed to protect them.

If you believe you were abused in a state-run children’s home or youth centre in Victoria, we want to hear your story. Kelso Lawyers has acted on behalf of many survivors of abuse in Victorian institutions, against the Government and third parties, and we can do the same for you.

Get the justice you deserve with Kelso Lawyers. We want to hear your story. Call (02) 4907 4200 or complete the online form before you accept payment from the National Redress Scheme.

Feature Image: Pexels