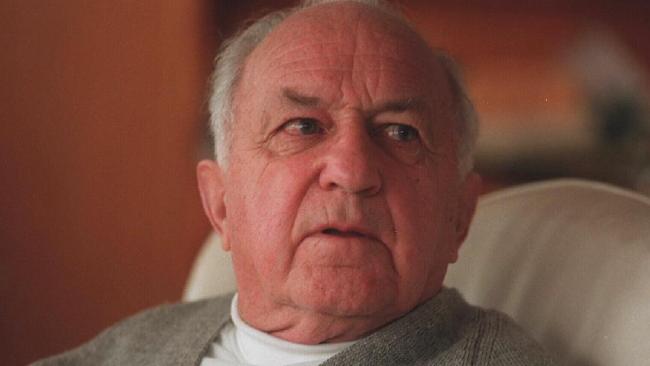

Father Kevin O’Donnell is one of the most notorious paedophiles in Australia.

Over the course of his almost 50-year career, he abused dozens of children. Some sources say he abused children from the moment he was ordained in 1942 “to the very end” of his career. He retired in 1992.

The worst part? His colleagues and superiors knew what he was doing.

Several victims reported the abuse to other priests but no one ever did anything to stop O’Donnell. He was allowed to continue on his merry way, leaving a trail of trauma and horror stories behind him.

The Catholic Church had a lot to answer for at the Royal Commission.

In this blog, we explore the long list of crimes O’Donnell committed against innocent, vulnerable children and unveil the travesty of just how long it took for O’Donnell to be exposed. Read on.

O’Donnell’s history

Father Kevin O’Donnell studied at Parade Christian College in East Melbourne and St Kevin’s Christian Brothers’ College in Toorak. In 1935, he entered Melbourne’s Corpus Christi Seminary to study for the priesthood.

Out of 378 priests to graduate from Corpus Christi College between 1940 and 1966, 14 went on to be convicted of child sexual abuse. Four others died before being convicted for their crimes.

He was in the company of sex offenders like Father Bill Baker, Monsignor John Day and Frank Little.

In 1942, he was ordained a priest for the Melbourne Diocese. He went on to fit masses, weddings and funerals in between sexual assaults for almost 50 years – and the Catholic Church admitted they knew about it.

Throughout his career, Melbourne’s church authorities were told about O’Donnell’s behaviour but decided to keep him in the ministry, enabling him to continue abusing children for decades. Plus, other priests knew O’Donnell was a danger to children but chose to do nothing about it.

Some priests said they “didn’t want to know about it”.

One sister dead, the other left to live with the trauma of O’Donnell’s actions

O’Donnell’s sick paedophilic behaviour tore a picture-perfect family apart – the Fosters. Two of Chrissie and Anthony Foster’s daughters, Emma and Katie, were abused by O’Donnell at Oakleigh’s Sacred Heart Primary School in the 1980s.

O’Donnell was the “chaplain” of the school. This allowed him to roam around the school and the playground, where he would ask children to help him do chores at the church or in his presbytery.

He would also see children for private “counselling” sessions.

Emma was abused in O’Donnell’s final years at Sacred Heart Primary School.

She didn’t tell her parents until O’Donnell was eventually jailed because she was “prohibited” from speaking ill of the clergy at school, but after O’Donnell’s disgrace, the prohibition was removed and Emma was free to tell her parents.

Her parents knew something was wrong. In the 1990s, Emma developed into a disturbed teenager and tried to commit suicide on multiple occasions. Katie was also acting out. She was drinking to numb the pain and in 1999, at the age of 15 years old, she stepped in front of a speeding car.

She was left with permanent intellectual and physical disabilities. She requires full-time care.

Chrissie and Anthony were devastated. They lodged a complaint with Melbourne archdiocesan sex abuse commissioner Peter O’Callaghan and a forensic investigation revealed both Emma and Katie had been sexually abused by O’Donnell.

Emma received a written apology from the Archdiocese of Melbourne. However, a written apology is often not enough to provide closure or comfort.

Over the next 12 years, Emma sank into a spiral of self-destruction. She was taking drugs and in January 2008, Emma died alone on her bedroom floor, cuddling a teddy bear she received on her first birthday.

It was a suspected drug overdose. She was 26 years old.

Bishop Anthony Fisher said people like Chrissie and Anthony Foster were “dwelling crankily over old wounds”

Six months after Emma’s highly publicised death, Pope Benedict arrived in Sydney for the Catholic World Youth Day celebrations. Chrissie and Anthony flew to Sydney with the hope of meeting the Pope and telling him personally about Emma and Katie.

Emma’s death had caused an uproar in Melbourne and Greater Victoria. Her story appeared prominently in the Melbourne press and evening news. Victorian parents had finally been warned about the negligence of the Melbourne Archdiocese and how they allowed a paedophile to “care” for their children for more than 50 years.

At a press conference, reporters asked the World Catholic Youth Day coordinator, Bishop Anthony Fisher, for comment on Chrissie and Anthony’s terrible suffering. He said people like the Fosters were “dwelling crankily over old wounds”.

It had been six months since Emma had died – not nearly enough time to grieve the death of a daughter.

Cardinal Pell showed a “sociopathic lack of empathy” while handling the Fosters’ case

In 2012, Anthony Foster told a Victorian Parliamentary Inquiry it should be mandatory to report any and all allegations of child sexual abuse to the state authorities.

“Any person, any person, suspecting the sexual assault of a child, should be required to report that suspicion to a state authority. Any person,” Anthony said.

He urged Victorian MPs to “lead the way for the rest of Australia” and implement legislative changes to provide justice for victims of abuse and protect all children. He also urged them to remove the statute of limitations preventing victims from seeking justice for older crimes.

Chrissie Foster then condemned the Catholic Church for failing to defrock O’Donnell even after he committed his crimes.

“Why was it so hard to get a priest [defrocked] for raping children, that he’d pleaded guilty to, for 31 years? We need honesty, we need truth. This is all we’re after, this is all we’re fighting for. Because if they were there, maybe this wouldn’t have happened to children, maybe this could be prevented in the future,” Chrissie said.

In order for the Catholic Church to regain its moral authority, Chrissie said the church would have to take a leading role in addressing allegations of abuse rather than hiding the crimes of paedophile priests and denying any involvement.

Anthony then spoke about the total lack of compassion shown by Cardinal George Pell in relation to their case. In 1997, Anthony and Chrissie met with Cardinal Pell and showed him an image of their daughter Emma harming herself. He couldn’t even muster a heartfelt response.

“Hmmm, she’s changed, hasn’t she”.

Cardinal Pell’s Melbourne Response program offered the Fosters a small amount of compensation for what O’Donnell did to their daughters.

The Fosters saw this as an insult. They decided to take a stand against the Archdiocese of Melbourne on behalf of all church abuse victims and take the claim to the civil courts for a more appropriate amount of compensation.

The Archdiocese’s lawyers fought the Fosters fiercely, but they eventually folded and signed a more adequate settlement with the Fosters.

“We experienced a sociopathic lack of empathy, typifying the attitude and responses of the church hierarchy.”

“There are simple things for us, moral questions about why does Kevin O’Donnell rest in the Catholic church priest crypt at Melbourne Cemetery, and is still honoured? Why is his name still on the plaque at our parish church?”

“Very simple things like that point to a much more systemic issue of continued reverence for people who have carried out terrible acts, and continued support for them in a priestly way.”

“But we’ve had no answers about why these things were reported. It’s all about prevention of scandal for the church, and reduction of financial liability. That’s what it’s about.”

Afterwards, Chrissie and Anthony spoke publicly about the experience and urged the Catholic Church to allow survivors of abuse to tackle the church for more compensation. They also went on to attend public hearings of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.

In May 2017, Anthony Foster died of a stroke at the age of 64 years old. The Victorian Government honoured Anthony with a State Funeral, which was held in the Melbourne Recital Hall. The hall was filled to capacity with 1,000 people.

O’Donnell’s charges

O’Donnell retired in 1992 but still continued to work part-time in metropolitan parishes. He still had direct access to children all over Melbourne and he was given a touching tribute by Archbishop Frank Little.

In 1994, a survivor known only as “Damian” went to the Victorian Police with encouragement from Broken Rites. Damian had been in touch with Broken Rites since 1993 but hadn’t reported the abuse because he was afraid he would upset his parents. His mother even insisted O’Donnell perform his wedding in the 1980s, which he reluctantly agreed to.

“About 1986, I complained to two priests in other parishes that I had been molested by a priest but they didn’t want to know the name of the offender. I also had some counseling in 1986 with a nun, who immediately wrote to the archdiocese about O’Donnell, but the archdiocese ignored the letter,” Damian said.

However, after reporting the abuse to the authorities, police made a surprise visit to O’Donnell’s home. He did not deny the allegations against him and he was charged with sexual assault.

The story was all over the news, and soon, victims from several parishes were contacting the police. Some callers agreed to make a sworn statement, while others refused because they didn’t understand prosecution procedures.

On the 7th of September 1994, O’Donnell was charged with 32 incidents of indecent assaults across four parishes. These incidents involved seven boys and one girl. He was released on bail for an upcoming hearing – the courts knew more victims were going to come forward.

With the court case underway, a priest from one of O’Donnell’s parishes asked parishioners to “pray for Father O’Donnell”. He did not mention the rising number of survivors.

A number of Melbournian priests talked about issuing a joint public statement in support of O’Donnell. A better-informed priest warned them there was mounting evidence against O’Donnell, and there was most likely going to be a conviction.

In 1995, O’Donnell was charged with the indecent assault of 12 victims, including ten boys and two girls. All victims were aged between eight and 15 years old and they were abused repeatedly over several years.

These were not the only victims, but the authorities decided not to wait for more victim statements. They decided to go straight to court with the existing 12 statements to get O’Donnell behind bars as soon as possible.

One of the victims, known only as Michael, said his Scout Leader had reported O’Donnell to the Vicar-General of the Melbourne Archdiocese, Monsignor Laurence Moran, around 1958.

“A couple of days later, O’Donnell told me he knew I’d dobbed him in and his boss had been out to see him… He said it was only a problem he’d ever had with me, and it was because he loved me,” Michael said.

A female victim known as Mary was abused by O’Donnell for three years in the 1950s but escaped his clutches when she was 16 years old. Mary escaped to a nunnery and didn’t leave until she was 25 – she said the loss of those vital years has had a devastating effect on her life.

“While I was still a nun, I told a Catholic priest, from the Jesuit order, about O’Donnell but he didn’t want to know about it,” Mary said.

On 11 August 1995, Judge Murray Kellam sentenced John Kevin O’Donnell to a total of 39 months in jail with a minimum of 15 months behind bars before parole.

He was released from prison in 1996. He was still a priest and still held the title of “Pastor Emeritus” (retired with honour). He died a year later and was buried among other Melbourne priests. Many priests also attended the funeral.

This man’s story is an absolute travesty. So many of O’Donnell’s colleagues protected him. Others simply didn’t want to believe it or hear about it. Then there were those who knew and decided not to act.

Survivors were disbelieved and ignored.

For 50 years, O’Donnell was allowed to travel from parish to parish, abusing children. The survivors mentioned in this story make up a small percentage of the true numbers. However, many chose not to submit a sworn statement or were too afraid to come forward.

Some may never tell their stories. We understand how hard it is to relive the trauma of institutional abuse.

At Kelso Lawyers, we take a caring and compassionate approach to each and every case. With our decades of experience, we have taken on the most institutional abuse cases in New South Wales.

We can help you achieve justice for the years of trauma you have been forced to suffer through.