Brisbane Grammar School. Established in 1868 and known for being the leading school for boys in Queensland.

St Paul’s School. An exclusive Anglican School named “School of the Year” in 2019 for Australian schools and non-government primary schools.

Both Brisbane Grammar School and St Paul’s School are highly prestigious with long, rich histories. Any Queensland-based parent would want their child to grow and learn in such a high-end educational environment.

In 2017, however, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse released a damning report about the two schools. The Commissioners found the schools’ long-time headmasters had “failed to act” when allegations of child abuse arose in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

The Commissioners also found there were no policies or procedures in place to dictate how staff members should handle allegations of abuse. In turn, these allegations were never investigated and nothing was done to ensure the students were safe.

Instead, the students were called liars and threatened with punishment.

While both schools have since taken positive steps to mend the damage that has been done, it is important not to forget the experiences of survivors.

In this blog, we delve deeper into the history of Brisbane Grammar School and St Paul’s School, the monsters who hid within their corridors, and the trauma experienced by some students.

Brisbane Grammar School

Image: Brisbane Times

Brisbane Grammar School is located at Spring Hill in Brisbane.

At the time of the allegations, Dr Maxwell Howell was the headmaster of the school and was responsible for employing the school counselor, Kevin Lynch, in 1973.

Lynch abused a large number of students behind closed doors. Despite the numerous complaints about him, Lynch stayed in his role as the school counselor for 15 years until 1988.

Students made complaints to senior members of staff including Dr Howell. However, it was like talking to a brick wall. In fact, the Royal Commission found Dr Howell took no action after receiving a complaint in 1981.

He did not investigate the allegations. He did not report it to the police or the school’s board of trustees. He failed in his obligation to protect his students.

“We find that during Dr Howell’s period as headmaster there was a culture at Brisbane Grammar where boys who made allegations of sexual abuse were not believed and allegations were not acted upon,” the Royal Commission’s report stated.

What’s worse is the fact Lynch went on to work at St Paul’s School from 1989 and 1997, where he continued to abuse students.

This chain of events could have been broken. Lynch could have been stopped at BGS. With better procedures and policies in place, the staff members would have known how to respond to allegations of abuse and perhaps Lynch would have been reported to police sooner.

Now, it’s too late.

Lynch committed suicide in 1997 before he could be charged for his many, many crimes.

“Almost immediately, Lynch commenced performing relaxation techniques that led to touching and then masturbation”

A survivor known as BQA started at Brisbane Grammar School in 1980 when he was in year eight. After four months, Dr Howell sent him to see Lynch because he was “easily distracted in class” and “not contributing to the school academically or in sports”.

BQA said Lynch started abusing him almost immediately. He told the Royal Commission Lynch would often touch and masturbate him. He was anally penetrated on two occasions. He said Lynch would sometimes give him tablets that made him feel drowsy or elated.

Some tablets stopped him from feeling stressed.

Lynch would also encourage BQA to skip school cricket games and classes. On one occasion, BQA was encouraged to skip school altogether. Lynch would authorise BQA’s departure from the school with the school bursar.

He was missing from class so often between 1980 and 1982, his teachers started to comment on his absence. No one ever asked why he needed counseling so often. He was even called into Dr Howell’s office to explain his absenteeism.

BQA said Dr Howell “wanted me to admit that I had been skipping school because I was unhappy at home”.

However, despite the abuse, BQA told the Royal Commission Lynch made him feel special. He loved Lynch like a father. Even though his classmates would often chant the words “poof, poof” when he walked past them in the hallways, BQA would still go to his regular “counseling” sessions.

Many students knew Lynch was touching boys.

In 1982, Dr Howell entered Lynch’s office during one of their counseling sessions. He saw BQA with his pants and underwear down. Dr Howell proceeded to call BQA a “sick individual” and told him to return to class.

BQA was then called in to speak with David Coote, the Deputy Headmaster, who questioned BQA about his “inappropriate relationship with Lynch”. BQA told Coote he loved Lynch more than his own parents.

BQA ended up leaving the school that same year.

In 1999, BQA met with the chairman of the board of trustees for Brisbane Grammar. At first, the chairman seemed shocked and concerned, but in later meetings, he was unhelpful and focused on protecting the school.

In 2001, BQA reported the abuse to local police. However, he was told Lynch had committed suicide and “no perp, no case”.

Red lights on Lynch’s door told students not to enter the office

Image: Unsplash

BQG started at Brisbane Grammar in 1981. He was just 12-years-old at the time.

He told the Royal Commission there was a “culture of fear and fear-driven respect” around Dr Howell. Because of this, the boys knew never to report things – not even sexual abuse.

BQG was abused three times a week (sometimes more) on a weekly basis for years. They would masturbate each other as a “relaxation exercise”, then Lynch would tell BQG their sessions had to be confidential.

Lynch was trying to normalise the abuse, and it worked. BQG saw Lynch as a father figure and never even considered reporting the abuse. In fact, they remained close until Lynch’s death in 1997 and BQG helped Lynch’s family carry the coffin at the funeral.

BQG told the Royal Commission Lynch’s office had two doors, both fitted with locks and intercoms. The intercom was fitted with a lighting system which had red and green lights. If the red light was on, students knew not to enter the office.

The students would have to wait for the light to turn green before going in. This ensured Lynch wouldn’t be caught abusing students.

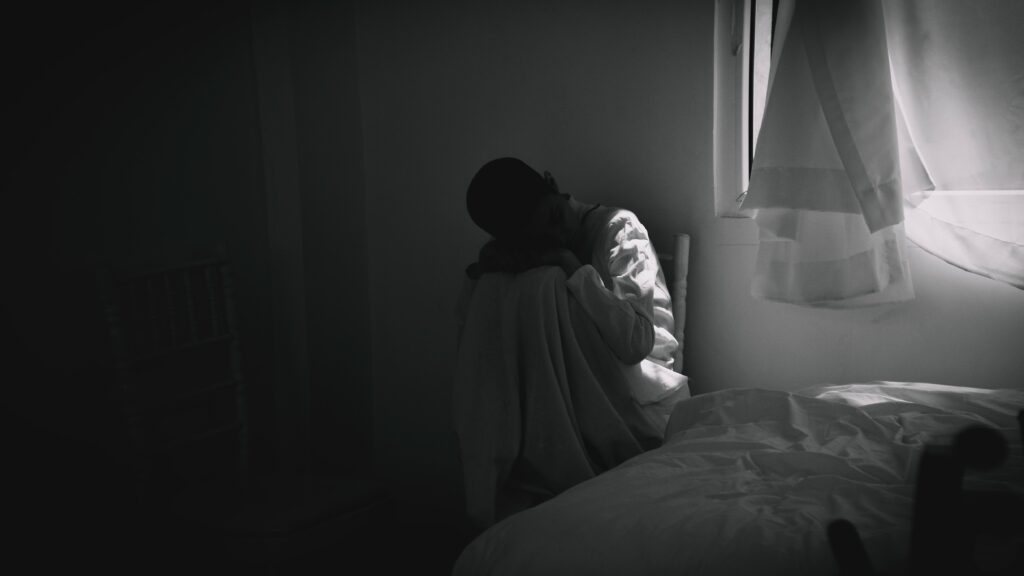

As an adult, BQG was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and needs to see a psychologist once a week. He has suffered from abandonment and trust issues, leading to two failed and “hollow” marriages.

Eventually, BQG decided to pursue civil proceedings. He gave up within a couple of years because the process was difficult and Brisbane Grammar School was “wearing him down”. He tried again in 2015 amidst the Royal Commission, but still found it burdensome.

Victim didn’t know what Lynch was doing, but he knew he didn’t like it

BQS started at Brisbane Grammar in 1986 after his parents divorced.

He was bullied relentlessly, but he never reported it. Like BQG, he was afraid of Dr Howell and didn’t understand that what was happening to him was wrong. Likewise, when he was sent to see Lynch for misbehaving in class, he didn’t know the sexual abuse was wrong.

BQS saw Lynch every day for a year. He was sexually abused at most, if not all, of their counseling sessions. He told the Royal Commission he didn’t know what was happening, but he knew he didn’t like it.

After one particular session, BQS sat down with his teacher, Ashleigh Byron, and broke down in tears. He told Byron he didn’t want to see Lynch anymore. The teacher didn’t ask any questions. Instead, he said:

“You’re just going to have to. You’ve got no choice in the matter. You have problems at home. You need to be doing something.”

From 1987 onwards, BQS struggled with drug and alcohol addictions. He spent time in rehabilitation facilities and was diagnosed with a brain disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, chronic depression and anxiety.

To this day, BQS has never considered himself to be successful. He has never been able to form healthy relationships and has attempted suicide on three separate occasions – all due to the trauma of the abuse he experienced and lack of support he received from those around him.

In 2001, he commenced civil proceedings and settled for $26,000. He said he felt “totally under-compensated” for the decades of trauma he has had to deal with.

St Paul’s School

St Paul’s School is located in Bald Hills in Queensland.

At the time of the allegations, Gilbert Case was the headmaster in charge of keeping the students safe. In his letter of appointment, protecting the children was even set out as one of his formal responsibilities.

In 1989, Case hired Lynch as the school counselor for St Paul’s. Lynch had just come from Brisbane Grammar School where he had abused countless students.

A witness at the Royal Commission said Case held a school assembly to introduce Lynch to the students. Case said he had a great reputation and called on the students to take advantage of Lynch’s counseling expertise.

After a year of working at St Paul’s, Lynch set up a system of lights to indicate when the room was occupied or free to enter – just like his office at Brisbane Grammar School. The students used to call them “traffic lights”.

One witness known as BRN tried to open the door when the light was read and noticed it had been locked from the inside. Lynch was up to his usual tricks.

But Lynch wasn’t the only offender at St Paul’s School.

Gregory Robert Knight was hired as a music teacher in 1981. There had been complaints about him at other schools, like Willunga High School in South Australia and at Brisbane Boys’ College.

Complaints had even been made to South Australian Police and the South Australian Department of Education, but they determined there wasn’t enough evidence of Knight’s misconduct for criminal proceedings.

In 1978, an inquiry was held into allegations of sexual abuse at Willunga High School camps. A victim claimed Knight had rubbed his penis during a 1977 camp. The Director of Educational Facilities rejected Knight’s denials and said he was “guilty of several counts of improper and disgraceful conduct”.

Knight was sent a letter notifying him he had been dismissed from the teaching profession, but he had already submitted his resignation to the South Australian Department of Education, so the dismissal was rescinded.

Knight was later hired at St Paul’s.

“You should never lie like that. You will ruin a man’s career if you tell lies like that”

Image: Unsplash

A survivor known as BSG attended St Paul’s on a scholarship between 1981 and 1985. He was able to attend on a scholarship with his brother.

Within the first three to four years at St Paul’s, Knight groomed, harassed and sexually assaulted BSG. He was targeted because Knight thought he was musically talented and the two spent a lot of time together. BSG even said they had a “unique” relationship.

The other boys noticed how close their relationship was. BSG would travel to and from school in Knight’s car, leading to constant taunts and bullying.

When BSG was in year 11, he found the strength to pull away from Knight and started calling Knight names himself. In 1984, he was called to Case’s office to be disciplined over the comments he’d made about Knight.

BSG told Case he hated Knight because of the ongoing abuse he’d experienced over the years and Knight deserved this kind of treatment. According to BSG, Case immediately shut him down and said:

“You need to be careful making statements like that. You should never lie like that. You will ruin a man’s career if you tell lies like that.”

Case also threatened to take BSG’s scholarship – along with his brother’s – away. BSG was given detention and sent on his way.

“Why are you lying? Knight is a good husband and father of 2 kids, you are causing a terrible slur on him”

BRV and BRT attended St Paul’s in the 1980s. The brothers were involved in the music program and Knight was their teacher.

In 1984, one of the boy’s friends told their mother Knight would search him for cigarettes by shoving his hands down his pants and touching him. He told his friends’ mother he wanted it to stop – he felt uncomfortable.

The boys’ mother, known as BRW, made an appointment to see Case within the week. She attended a meeting with Case and two other male teachers where she was made to stand the entire meeting.

Her sons were invited into the room and confirmed their friend’s complaint about Knight. According to BRW, Case then said, “why are you lying? Knight is a good husband and father of two kids, you are causing a terrible slur on him”.

She asked what was going to be done about the complaint.

The men responded “there is nothing to be done, because there is nothing going on”.

From then on, Knight never touched the boys again, but Case also made sure her sons never received any more school awards despite their involvement with the school, and Case never called BRW her by name.

What has happened since?

Image: Unsplash

In 2004, Knight was charged with sexually assaulting BSG. He was convicted by the jury, then exercised his right to appeal. He was unsuccessful.

The Royal Commission also concluded the headmasters of Brisbane Grammar and St Paul’s did not attempt to report Knight or Lynch. Neither of the men made steps to protect their students’ wellbeing.

Since the Royal Commission’s final report, both schools have added a statement to their websites.

“If you were a victim of abuse while you attended St Paul’s School, we wish to extend a personal apology to you,” St Paul’s statement says.

“The lack of proper systems, policies and practices in the 1980s and 1990s let you and other young people down terribly. People who should have been trustworthy betrayed and abused vulnerable young people. The crimes should never have occurred and certainly should never have been allowed to continue for as long as they did.”

“We are deeply sorry.”

In addition, both schools have joined the National Redress Scheme. A large portion of the compensation for victims will be paid by the Diocesan Insurance, while the remainder will be paid by the schools.

St Paul’s have also offered to refund the school fees paid by the victims, as per the Anglican Diocese of Brisbane’s proactive fee refund policy.

Brisbane Grammar School, however, does not offer refunds.

“Brisbane Grammar School will continue with its approach to redress and compensation since 2000, which includes a personal apology from the current leadership of the school, agreed compensation payments and counselling,” the school said in a public statement.

“The school can never do enough to mend the hurt caused by the actions of Kevin Lynch, but will continue its endeavours to bring some measure of healing to those abused by him.”

While some recognition has been given to the survivors of Brisbane Grammar and St Paul’s School, it has not been a smooth road. Those who pursued civil claims before the National Redress Scheme were put through the wringer by their respective school, or dramatically under-compensated.

The process was stressful, disappointing and retraumatising.

However, it doesn’t have to be that way. Since the establishment of the National Redress Scheme, institutions like Brisbane Grammar and St Paul’s are more willing to provide compensation and apologies.

Feature Image: Unsplash