The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse exposed a deep and disturbing history of abuse across Australia’s schools. From elite private institutions to smaller regional public schools, the investigation uncovered how various schools failed to protect their students from sexual abuse.

Here, we expose some of the worst offenders across the country, shedding light on the systemic failures that allowed abuse to happen, and exploring the long-term impacts it’s had on the victims.

The Royal Commission’s shocking findings

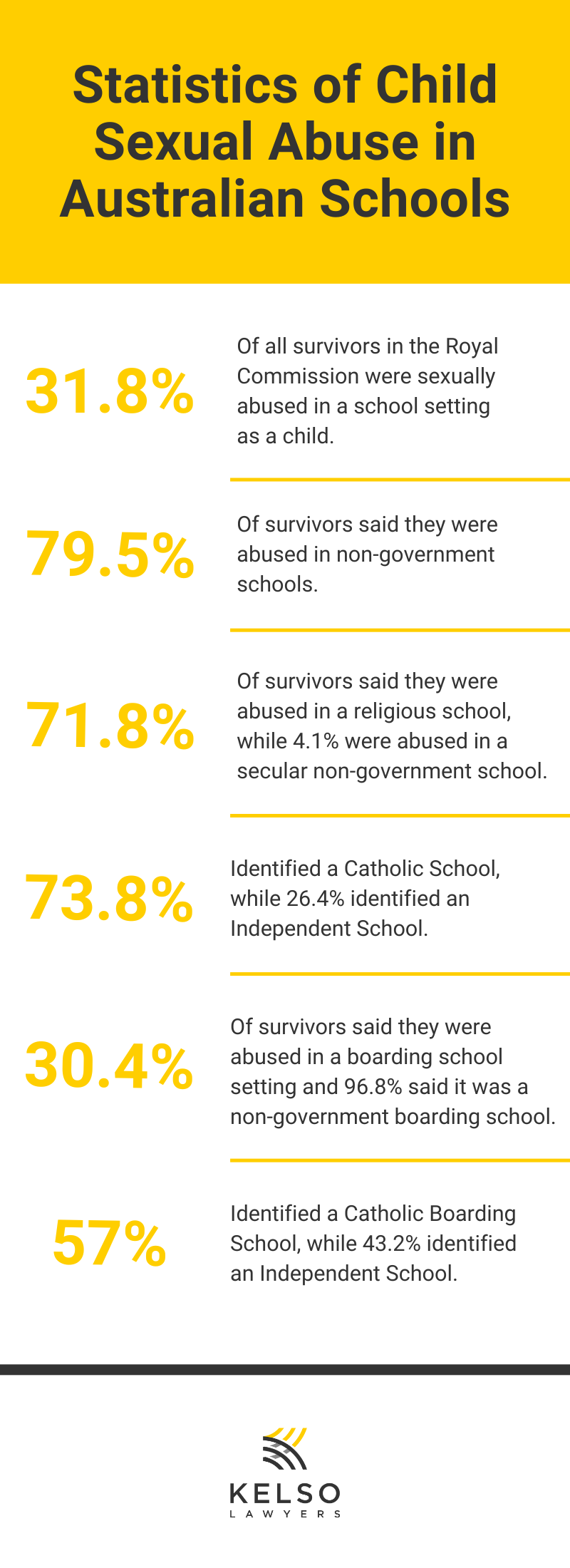

The Royal Commission’s investigation revealed that almost one in three survivors of institutional abuse reported being sexually abused in a school setting. Of these survivors, the majority identified non-government schools, particularly Catholic and Independent schools, as the locations of their abuse.

The report uncovers repeated instances of abuse, often involving multiple perpetrators, where schools failed to act or took insufficient action to stop it.

Among the most troubling cases were those in NSW and Victoria, where prestigious institutions allowed abuse to continue under their roof, despite multiple complaints and warnings. The Commission’s findings shocked the nation and highlighted the urgent need for reform across all Australian schools.

Ben Venue Public School, New South Wales

Ben Venue Public School in Armidale became a tragic symbol of how unchecked abuse can thrive in institutions meant to protect children. During the 1970s, the school was home to not one, but three active paedophiles, all teaching at the same time: John Ferris, Ian Berryman, and even the principal, Peter Garland.

As the principal, Garland had the most authority and protection within the school. He was known by students as “the feeler” because of his predatory behaviour. Garland would lock children in his office and touch them or force them to touch him. His actions were well-known within the school, but he was virtually untouchable as the principal.

Despite at least five families reporting Garland’s behaviour to NSW police, no charges were ever laid. Police dismissed the allegations, claiming Garland was a “respected member of the community”.

The Education Department also brushed off concerns, telling one family their child wouldn’t be believed because it would be “their word against the principal’s”.

It wasn’t until 2014, years after his death, that NSW Police finally launched a serious investigation into his actions. At least 15 students came forward with allegations, though the number of victims continues to rise.

Despite his legacy of abuse, Garland was awarded an Order of Australia Medal in his retirement, further illustrating how the system failed to protect children under his care.

The survivors of abuse at Ben Venue Public School have faced lasting emotional, psychological, and academic consequences. Many reported significant declines in their mental health, academic performance, and personal relationships. The abuse they suffered at the hands of trusted school staff has left scars that will last a lifetime.

Knox Grammar School, New South Wales

Knox Grammar School, an exclusive private school in Wahroonga, NSW, is one of the most well-known offenders in the Royal Commission’s report. Multiple victims came forward with stories of sexual abuse by staff members, including Roger James, a teacher who was allowed to continue teaching despite numerous complaints against him.

But the list of offenders doesn’t end there. Various teachers, such as Barrie Stewart, Adrian Nisbett, Craig Treloar, and Damien Vance, were convicted.

The most shocking part of the Knox Grammar case was the school’s leadership by Dr Ian Paterson, who prioritised protecting the institution’s reputation over the safety of the students. Complaints were dismissed, allegations were ignored, and perpetrators were allowed to remain in their roles.

One survivor told Commissioners:

“I see Paterson as a bully and a coward whose primary consideration was to maintain the reputation of the school at the expense of its students. Looking back, I can see that the welfare of the students was not a priority of the school at the time of the offences perpetrated against me (and other students).”

The school’s culture, which held authority figures in high regard, discouraged students from speaking out, and when they did, their voices were silenced. The failure to address repeated abuse allowed the situation to escalate, leaving many students vulnerable.

The Hutchins School, Tasmania

Between 1963 and 1970, multiple perpetrators—including the headmaster, David Lawrence—were accused of grooming and sexually abusing students at the Hutchins School in Tasmania.

Lawrence allegedly used private tutoring sessions as an opportunity to abuse a student, and the school failed to address the allegations, even when other teachers like Spencer George Lyndon Alfred Hickman were dismissed for similar conduct.

The survivor known only as AOA said he didn’t know what was happening in those private tutoring sessions, but felt “special and wanted” at a time when he needed the affection.

“Every lesson was more or less the same. He would pull me in close and place his arm around my waist and then place his hand on or around my groin, and he would then proceed to tutor me in French,” AOA said.

“He would casually reach through my trousers as I read my French lessons.”

The Hutchins School’s failure to take action was part of a pattern seen across many schools, especially non-government ones, where institutional culture put the school’s reputation before the safety of students. Teachers who spoke out were ignored, and the allegations were buried. This failure to protect students allowed the abuse to continue and left a trail of trauma in its wake.

Geelong Grammar School, Victoria

Geelong Grammar School, one of Australia’s most prestigious schools, was also named in the Royal Commission for its failure to address child sexual abuse.

Multiple survivors came forward to report abuse that occurred between 1956 and 1989. Despite several complaints, the school’s leadership did little to address the situation, and the perpetrators were allowed to continue their actions, including Graham Leslie Dennis, John Hamilton Buckley, Stefan Van Vuuren, Philippe Trutmann, and John Fitzroy Clive Harvey.

One survivor, Philip Constable, was a boarder in 1956 from the age of eight. He told the Commission his house master, Graham Leslie Dennis, would have him sneak out to see him most nights. Dennis would “play with his own genitals” and tell the boy he loved him.

“I don’t know how to convey in words the absolute sense of being unable to escape this hell for three long years. As a little boy, that length of time seemed like an eternity. There was no light. It was like being buried alive,” Philip told the Commission.

In this case, Philip told his parents about the abuse, and Dennis was convicted.

The failure of Geelong Grammar to act on the complaints highlights a systemic issue in many Australian schools, where leaders have chosen to protect the school’s reputation instead of safeguarding the children under their care. The abuse at Geelong Grammar wasn’t an isolated case; it was part of a disturbing pattern that has been uncovered in many elite private schools across the country.

Brisbane Grammar School and St Paul’s School, Queensland

The Royal Commission’s report highlighted serious failures in how Brisbane Grammar School and St Paul’s School responded to claims of abuse by staff members like Kevin Lynch.

He worked as a teacher and a school counsellor from 1973 to 1988. Despite many students coming forward with abuse claims, the school did nothing.

One parent reported that Lynch had abused their son, but the school never investigated or contacted the authorities. This reflects a culture at the school where allegations were ignored, and students were not protected.

At St Paul’s, Lynch continued his abusive behaviour as a school counsellor from 1989 until his suicide in 1997. When students reported the abuse to headmaster Gilbert Case, he dismissed their claims and threatened them with punishment if they spoke out. The school had no systems to monitor staff or take action when students complained, allowing the abuse to continue.

Both schools failed to protect their students and allowed abusers to stay in their roles. These cases show the serious problems in child protection within Australia’s educational institutions.

St Ann’s Special School, South Australia

St Ann’s Special School in Adelaide has become one of the most notorious schools in South Australia due to its catastrophic failure to protect vulnerable students from a known predator.

The Royal Commission found that between 1986 and 1991, convicted paedophile Brian Perkins was employed as a bus driver at the school—a role that gave him unsupervised access to children with intellectual disabilities; many were non-verbal or had limited ability to communicate.

Shockingly, the school principal, Claude Hamam, failed to carry out basic employment procedures. He didn’t check Perkins’ references or conduct a police check, which would have revealed multiple prior sexual convictions. He didn’t notify senior officials or the school board when abuse allegations surfaced in 1991.

Perkins was allowed to volunteer around the school, often unsupervised, and even provided “respite care” to students without formal approval, creating more opportunities for abuse.

Police also failed spectacularly. Despite having damning evidence (including naked photos of students) they did not arrest Perkins, who fled the state and remained free for over a decade. During this time, many parents remained completely unaware of the abuse their children may have suffered.

This scandal was compounded by a slow, insensitive response from the Catholic Church, which used a controversial “group approach” to compensation rather than applying its own Towards Healing process. Many families felt silenced, ignored, and hurt by a system that should have protected their children, not abandoned them.

St Ann’s isn’t just one of Australia’s worst schools because abuse happened — it’s because every level of authority failed to stop it.

Why abuse was allowed to happen at these schools

Image: Unsplash

Several key factors contributed to the high prevalence of abuse in Australian schools, particularly in private and religious institutions.

Institutional cultures of silence and protectionism

Many schools, particularly non-government ones, fostered a culture that put the institution’s reputation ahead of student safety. This meant that complaints of abuse were often ignored—from students and their parents—and perpetrators were allowed to continue working with children.

Governance failures

In many cases, the school leadership was not held accountable for failing to protect students. Long-serving heads and ineffective boards allowed abuse to continue without intervention. The lack of proper oversight and accountability allowed perpetrators to thrive unchecked.

Boarding school risks

Boarding schools were particularly prone to abuse due to the isolation of students from their families. With limited supervision and extended hours spent on school grounds, perpetrators had more opportunities to groom and abuse students. The Royal Commission found that non-government boarding schools were particularly vulnerable.

Failure to protect students

Many schools failed to implement or properly enforce child protection policies. Even when such policies existed, they were often poorly communicated to staff or inadequately enforced. Teachers and administrators usually lacked proper training to recognise the signs of abuse and failed to act when allegations were made.

The long-lasting impact on survivors

The damage caused by child sexual abuse in schools goes far beyond the immediate trauma. Survivors often carry the emotional and psychological scars for years, with far-reaching consequences.

Declining academic performance

Many survivors told the Commission that their academic performance suffered dramatically following the abuse. Once high achievers, these students struggled to focus and often experienced a decline in grades and self-confidence. Some dropped out of school early, limiting their professional development later in life.

Psychological and emotional trauma

The emotional toll of abuse often led to long-term issues with mental health. Survivors reported feelings of depression, anxiety, and a profound sense of helplessness. Many struggled with forming healthy relationships and trust issues well into adulthood.

Struggles with social and career development

The effects of abuse were also felt in survivors’ personal and professional lives. Many survivors found it difficult to move forward with their careers or engage socially due to the lasting emotional damage caused by their abuse.

Justice is long overdue—we need to hold institutions accountable for their failures

The worst schools in Australia, from Knox Grammar to The Hutchins School and Geelong Grammar, have shown the world how the failure of leadership, governance, and accountability can allow child sexual abuse to persist for decades.

While these schools have made strides in improving child safety standards, the instances of abuse are far from over across Australia. Many government and non-government schools still fail to protect their students adequately. It’s not uncommon to see school sexual abuse in the news, even today.

We believe survivors deserve justice and are dedicated to helping you hold institutions accountable for their failures. Our expert legal team is here to support you through every step of your case, from understanding your legal options to navigating the complexities of seeking compensation.